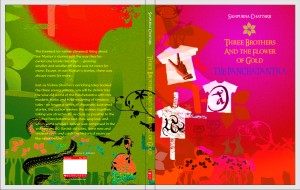

Three Brothers and the Flower of Gold

In 2008, Three Brothers and the Flower of Gold, Sampurna’s modern retelling of the ancient Sanskrit text The Panchatantra came out from Scholastic India.

Pegged as “the first complete Panchatantra for children – relevant, real and right for the twenty-first century”, Sampurna’s version tells the story from the point of view of the three princes for whom the original text was ostensibly written. In all previously existing versions, the three “ignoramuses” for whom Pandit Vishnu Sharma tells the tales that comprise The Panchatantra are outside the frame of the main text. In Sampurna’s version, they – primarily, the oldest of three boys – become the storytellers.

As the author put it on the Scholastic website:

“Retelling The Panchatantra was like wandering into an enchanted labyrinth with a ball of string in one hand and a pen in the other. The structure of this ancient text was so cunning, so intricate and so beautifully constructed, that I realised how much was lost in telling the tales in isolation, as is usually done. It was the intricacy and the inter-connectedness of the five books that I wanted to maintain in my version. To that I brought the newness of my narrator’s voice – namely, the eldest of the three princes for whom the stories were originally written, and who are normally viewed as lying outside the text. I decided to make them integral to the text, as participants, three unruly, hyper-imaginative, wilfully ignorant but secretly intelligent boys who realise for themselves the power and the truth of the stories their teacher tells them. I have to say that in the process of writing Three Brothers and the Flower of Gold, I grew extremely fond of V-Boy, UberCool and Amazer, and wished I could have stayed with them in their adventures beyond the confines of this book!”

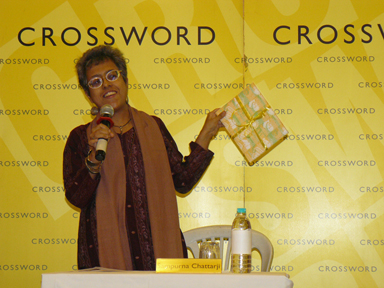

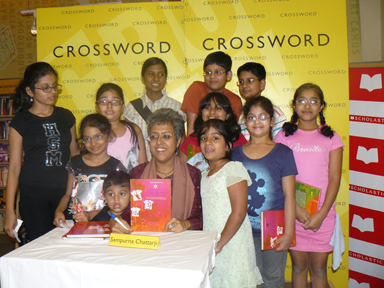

The book was launched with much fanfare – and a puppet show based on the text – at Crossword, Kemps Corner, Mumbai on Children’s Day, November 14, 2008.

Some photos from the launch:

The text of a talk given by Sampurna Chattarji, in which she shared some of her challenges and strategies while writing Three Brothers and the Flower of Gold:

“I’d like to begin by saying that the retelling of a classic such as The Panchatantra is perhaps the place where the two roles of the ‘storyteller’ and the ‘story-writer’ come together…Here is a work of fiction that began in an oral tradition, where the stories changed at every telling. Here also is a work that travelled across countries, cultures and languages, losing and gaining in migration not just characters and narratives but moral impulses and audiences. And while the oral tradition is one where anonymity is the norm, the written demands an ascribed authorship, even if the authorship is notional, fictional or symbolic as in the case of Vishnu Sharma, the author of The Panchatantra. The ‘original’ version is lost…and yet the tales have survived nearly two millennia. What, then, does this mean for a contemporary writer like me, in terms of ownership of this vast, complex and travelling text, in terms not just of writerly strategies of tone, character, and authorship, but also of oral strategies of improvisation, relevance, and the inflections of voice, gesture, expression and presentation?

The first movement for me was from being the ‘audience’ of The Panchatantra to being its ‘narrator’. As a child, as most children and adults here will testify, I received The Panchatantra piecemeal. Here were stories everyone knew – the crab and the crane, the lion and the hare, the fox and the drum. These were moral tales – that was very clear to me as a child. But what was never apparent was that these tales were not simply single floating stories with morals attached like the tails of kites, but in fact stories that came from a master-text that was a complexly-structured, tightly-woven, beautifully-written book! And not just one book, five books, each with a specific theme. It was only as the potential writer of a new retelling that I discovered, and was blown-away by, the artistry that went into The Panchatantra in its entirety. And part of my desire while writing Three Brothers and the Flower of Gold was to some extent convey that sense of scale, the five-pronged, multi-layered, story-within-a-story architecture of The Panchatantra, a well-kept secret that now seemed to me part of an adult conspiracy against complexity and context! I felt it was important that I not just present, but re-present some of the old familiar stories and a host of – to me – unfamiliar stories, within that schema and use the format of the five books as a liberating constraint. A constraint in terms of form, liberating in terms of content, point-of-view and tone.

However, even as my reading of Chandra Rajan’s excellent translation of Purnabhadra’s 1199AD text opened up this wonderland of riches hitherto unimagined, it also had the effect of making me wonder how on earth I could present it in a way that would connect to the young reader of today. While the story-writer in me was determined to pay homage to the sophistication of the original literary narrative strategies, the story-teller in me was unsure what nuance, inflection and expression would enable me to engage the audience of now, for whom the moral tales of our collective childhood would already be crippled by seeming too moral, too childish. This is the problem that took the longest time for me to solve. Until I came to the realisation that I wanted to tell the story again, as if for the first time, through the voices of three characters who were, in the original, outside the purview of the text itself, namely – the three princes, the King’s sons, who were “totally averse to the very name of learning”, as we are told in the Preamble. Vasushakti, Ugrashakti and Anantashakti are, as the text pithily informs us, “supreme ignoramuses”. I decided that these three, the original audience for Vishnu Sharma’s commissioned work of enlightenment and education, were going to be the narrators of my version. I was going to make them travel the same arc from audience to narrator that I had embarked upon myself. From being the ‘reasons’ for the text to exist, I wanted to propel them into the text itself. Resistant, participatory, interrogative, these three brothers would be my fictional authors, much as Vishnu Sharma is presented as the perhaps-fictional author of The Panchatantra. My retelling would be, as I remember writing in an early mail to my editor, Sayoni Basu – “a journey from ‘ignorance’ to ‘wisdom’ as chronicled by one of the three sons”.

In the brotherly trio I found my link to the audience of now. Also, and this was a selfish motive, these three boys would be the characters I could invent and embellish from scratch. One of the limitations of retelling is that one feels a certain responsibility towards the source text – to what extent can one, or should one, depart from the original? How much leeway does one allow oneself with such seminal texts? How much of it is a misplaced ‘reverence’ towards the source text, and how much of it a genuine desire to convey the original impulses of that text? The three brothers, of whom I knew nothing more than their names and their status as supreme ignoramuses freed me and gave me a huge creative push that allowed me to negotiate the vast territory of the Five Books in a completely fresh way. They became in essence, the bearers of my storytelling and story-writing impulses, they gave me tone, character, dialogue, nuance, inflection, expression – in short they became the audience as narrator, speaking in the language of the moment, but telling the stories of all-time.

Their role in the book as my surrogate sutradhars is not passive. They move from open resistance to an engagement with the Master’s stories, to active discussion and disagreement among themselves on what the stories mean. The boys are growing up before our eyes, they are, in a way that I hope is more organic than imposed, enacting the original purpose of The Panchatantra as a niti-shashtra, as a means to “awaken the intellect”. As V-Boy says, “We were only stupid at some things!” Their aversion to learning may be a conscious act of rebellion, their inability to absorb what is taught may be a reflection on the methods of teaching rather than their own ineptitude. Vishnu Sharma’s method is new – as entertaining as it is educative – and the boys, particularly V-Boy and Amazer find themselves taking to it like fish to water. Uber is the hardest to win over, and in the conflicts that erupt between the three brothers I found a seamless way of moving from the theme of one book to the other – from the Losing of Friends to the Gaining of Friends in Books One and Two, from the deep-rooted enmity of Crows and Owls in Book Three to the Loss of Gains in Book Four to the Rash Deeds of Book Five. V-Boy tells only those stories that are pertinent to his own predicaments as the oldest brother in the story, and he is also the one who comments on his Master’s craft even as he attempts to duplicate it in his retelling. V-Boy is the one who delights in Amazer’s childish and childlike belief in the reality of the stories, and in his openness and receptiveness – the merits of any good audience! The Flower of Gold that the jackal Karataka talks about is not symbolic to Amazer. To Amazer, the youngest of the three, the power of the fairytale is real.

As Chandra Rajan points out in the excellent introduction to her translation, names are not incidental in The Panchatantra. Nearly all are “descriptive of some essential trait, physical or otherwise of the characters”. It is V-Boy who realises this for himself in Part Four of my retelling, where he talks to Agni, the Flaming Mare at the Bottom of the Ocean and really understands for the first time the fleeting thought he had voiced right at the beginning of the book – “Names are power…When would we live up to the meaning of our names?” The moral education of The Panchatantra is not a moralistic one, not an overly-idealistic one, but a practical, self-motivated one, a lesson on how to live within one’s particular context, situation, role and personality in relationship to the world of the moral, the emotional, the imaginary and the real.

It is Uber, the middle brother who arrives at his own awakening last, but in a way that is true to the disturbing, dream-like mode of Book Five. His narration has a tone that is different from the four books that precede it, while remaining integral to the journey the audience must make – for themselves.

So my strategy as a writer attempting to create a new fiction out of received material was really that old oral technique that is, and remains, contemporaneous and relevant – point of view. By finding an answer to the question “Who will be the teller of my version”, by following in the footsteps of centuries of oral revisions, alterations, expansions, condensations, by inhabiting the voice and attitudes of three young boys, I found a way of doing what the storyteller of old would do with his mere physical presence – I found a way of establishing rapport with the unseen audience of this written-down and, to that extent, fixed text I now hold in my hand. And by following the structure of the emboxed tales, I moved from the original audience of the three princes through a whole progression of changing in-situ immediate audiences within the book to the modern reader, sitting before me today.

As I like to tell kids at my readings in schools, here is a book that is not simply that old Panchatantra that they might think they have outgrown, but rather a new book, about growing up, a book about friendship, how we make friends, how we lose friends, a book about the importance of intelligence and courage, and above all – a book about learning to think for yourself, as its protagonists, the Three Brothers, do.

I will conclude by saying that when I agreed to do this book for Scholastic, I had no idea that a full four hundred and thirty-eight years after Sir Thomas North’s first Elizabethan English version, I would be carrying on a tradition that found its way into fifty different languages, the narrative literature of the Middle Ages in Europe, from the Arabian Nights to the Fables of La Fontaine, and that tells, perhaps more than any other text, the story of our connectedness.”

In November 2008, Sampurna read from Three Brothers in what was the inaugural event at Bookaroo, India’s first Children’s Literature Festival at Sanskriti Kendra, New Delhi. Some pictures of the outdoor event.

Leave a comment